As a hardened reader of sensationally horrible deaths in the Victorian press, you would think that very little would shock. Yet there is a category of mortuary stories that recently has given me pause. I refer, of course, to stories involving writs of replevin on corpses.

What?

Here is the basic legal definition.

Replevin is an action or a writ issued to recover an item of personal property wrongfully taken. Replevin, sometimes known as “claim and delivery”, is an antiquated legal remedy in which a court requires a defendant to return specific goods to the plaintiff at the beginning of the action. The advantage of a writ (order) of replevin is that it deprives the defendant of the use of the property while the case is awaiting trial, therefore increasing the likelihood of a quick settlement.

But what does this have to do with corpses?

REPLEVYING A CORPSE

A Dead Woman’s Body Held for a Board Bill.

Trouble Between Foster Geggs and Mrs. Frost, His Landlady.

A Difference of Fifty Dollars Provokes a Strange Suit.

Difficulties Experienced by a Constable in Serving a Writ.

‘Squire Sanderson issued a writ of replevin yesterday for the remains of the wife of Foster Geggs, a merchant of New Lexington, Ohio. They were detained by a Mrs. Frost, a keeper of a boarding-house at No. 322 Walnut street. Constable Frank Dossman served the papers, and, after a great deal of trouble, the body was secured.

Five weeks ago a gentleman and lady arrived in this city from New Lexington, Highland County, Ohio. They were Mr. and Mrs. Foster Geggs. They applied to Mrs. Frost for board and lodging, and were accommodated. The lady appeared to be in bad health, and

THEIR MISSION TO THIS CITY

was the search of medical aid for Mrs. Geggs, who was suffering from a complication of diseases. She appeared to regain her health for a time, but a week ago she had a relapse. Early yesterday morning her sufferings were released by death. When daylight had arrived Geggs sent for Estep & Meyer, the undertakers. They embalmed the body, and, incased in a handsome coffin, it was ready to be shipped to New Lexington for burial. Shortly after noon the undertakers’ wagon arrived to take the remains to the depot, but Mrs. Frost refused to allow them to be removed. She claimed that Geggs owed her $50 for board and lodging.

HE ACKNOWLEDGED THE INDEBTEDNESS,

but not to the amount she claimed. He offered to settle for $25. This offer the woman spurned. He pleaded with her to allow the undertakers to remove the body of his dead wife, but she shook her head and said no. She wanted her money, and was going to have it, if she had to hold the body for a week. Several of the boarders tried to persuade her to release the remains, but it was of no used. Finally, Geggs threatened to swear out a writ of replevin. Mrs. Frost laughed at the idea, and dared any Constable to enter her house. Seeing no other way to secure the body of his wife, he appeared before ‘Squire Sanderson and swore out

THE WRIT OF REPLEVIN.

The ‘Squire detailed Constable Dossman to serve the papers. When he arrived he found the door of the house locked and barred. He rang and knocked for admittance, but Mrs. Frost refused to admit him. He next tried the windows, but could not in any way gain an entrance. The alley way was the only resort, and on this side the Frost woman did not look for the Constable to enter. After scaling a high fence he found open the rear door. Having gained admittance, he found the corpse in the parlor. The writ was served on Mrs. Frost, and she reluctantly opened up the front door and

THE COFFIN WAS REMOVED

to the undertaker’s wagon, which was still in waiting. The remains were driven to the Grand Central Depot, from whence they were taken to New Lexington last night. The writ also called for several valise and trunks, which were also secured. The interesting and sensational suit will be heard Monday December 27, by “Squire Sanderson.

This is the second instance in this city where a corpse was secured only on a writ of replevin.

ANOTHER CASE

About two years ago the wife of Johnnie Ryan, the Fifth-street concert hall man, swore out a writ for the body of her baby that was buried in St. Joseph’s Cemetery on the Warsaw pike. Mrs. Ryan wanted the remains removed to another cemetery, but the Superintendent refused to give up the body, claiming that she owned for the burial lot, and the digging of the grave. She appeared before “Squire Sanderson and swore out the writ. Constable Frank Johnson, with a squad of Special Constables, served the papers. A number of spades were secured and the body of the child was resurrected. The Cincinnati [OH] Enquirer 17 December 1886: p. 4

Popular thought held that a body was not property and could not be stolen.

The common law recognizes no property in anybody in the dead, though it does recognize the property in the shroud and other apparel of the dead as belonging to the person who was at the expense of the funeral. Cincinnati [OH] Daily Gazette 17 April 1880: p. 8

and

But whatever may have been the rule in England under the Ecclesiastical law, and while it may be true still that a dead body is not property in a commercial sense of that term, yet in this country it is, so far as we know, universally held that those who are entitled to the possession and custody of it for purposes of decent burial have certain legal rights to and in it which the law will protect. Indeed the mere fact that a person has exclusive rights over a body for the purposes of burial, necessarily leads to the conclusion that it is property in the broadest sense of the term, viz., something over which the law accords him exclusive control. (Larsen v. Chase, 50 N. W. 238, cited in “Property in Dead Bodies,” Walter F. Kuzenski, Marquette Law Review, Issue 1, Vol. 9, December 1924)

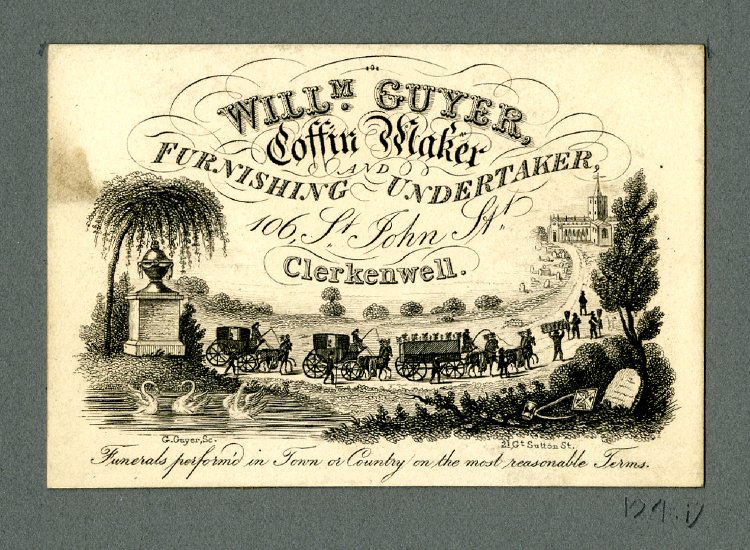

However, in real life, bodies were often held for ransom. The threat of either retaining a corpse, of publicly displaying it, or of burying it in a pauper’s grave was used in all kinds of circumstances to extort money, legally owed or not. A decent burial was a serious business; even the poorest would go to great lengths to have the trappings of a “proper” funeral, rather than a pauper’s rites, with burial in the Potter’s Field.

Some hospitals apparently had VIP undertakers on the early 20th-century equivalent of speed-dial. I assume the undertakers paid handsomely for their priority status.

ON REPLEVIN WRIT

John Lund Secures Possession of Wife’s Corpse.

Undertaker Holds Body of Woman Who Died at Hospital and Refuses Possession.

After he had been forced to take out a writ of replevin to secure the corpse of his wife, who died yesterday morning at U.B.A. hospital, John Lund, an Englishman, was permitted to proceed with the arrangements for the funeral. Mrs. Lund died yesterday morning and, in accordance with a custom common in the hospitals, a nurse immediately notified Edward J. Corkery, an undertaker at 524 South Division Street. Corkery called for the body.

Soon afterward Metcalf & Co., who had been notified by the husband, went for the body and were referred to Corkery, who refused to give it up unless paid for his trouble. Lund went to the prosecutor for a warrant for kidnaping, but the prosecutor advised him to take out the replevin papers, and made them out himself. The body was taken by a constable late last night on the writ and removed to Metcalf’s establishment.

The funeral will be held from the residence of Andrew Olesen, 264 Ann street, Saturday afternoon at 2:30. Grand Rapids [MI] Press 5 September 1907: p. 8

It is a nice point whether a dead person can be kidnapped, but the prosecutor obviously made the right call.

With this next case, we meet Mr. John B. Habig, a well-known Cincinnati character and keeper of the Cincinnati public morgue for 20 years, in a highly discreditable incident.

AN EXTRAORDINARY REPLEVIN

An Attempted Case of Extortion

The body of the aged gentleman who fell dead in front of No. 88 Twelfth street, on Thursday morning, as reported in the Gazette of yesterday, was identified yesterday by his son as that of William Hall, as was surmised. The young man, William C. Hall, an engineer on the I.C. & L Railroad, came to the city yesterday and after identifying the body at Mr. John B. Habig’s undertaking establishment, No. 183 West Sixth street, ordered it removed to Soards, a few doors east for shipment and interment, at the same time offering Habig $10, as payment for keeping the corpse. But Habig was not that kind of man; he wanted more than $10 for keeping the body a day and a half, and demanded $40. The young man refused, claiming that the demand was extortionate, and was told that he must pay it, or he could not have the corpse. This was late last night, but Mr. Hall posted off to ‘Squire True, who, fortunately, was in his office trying the case of the Hamiltonian horse-killers, and who at once gave Mr. Hall the requisite magisterial assistance. Constable Green was armed with a writ of replevin and at once started off after the body. Shortly before midnight the strong arm of the law grasped the corpse and transferred it to Soards’ establishment, from whence it will be shipped to Mt. Carmel to-morrow morning. If Mr. Habig wishes to rid himself of the richly deserved odium which much attach to the act, he must rise and give a satisfactory explanation of his exorbitant demand.

In years gone by the deceased kept a well-known livery stable on Sycamore street below Fourth. Cincinnati [OH] Daily Gazette 8 August 1874: p. 4

The Cincinnati Enquirer also reported on the case, adding the detail that “The daughter of the deceased remarked that she did not wish Habig to bury the body because he had sent a drunken attendant with her when she went to view it.” The newspaper added, “Mr. Habig has added to his reputation, but not to his stock of money, or we have been sadly misinformed.” Yet when he died, the Enquirer wrote favorably of him, stating in his obituary: “On down the pages of crime’s annals in this vicinity the name of Habig is so closely linked with these crimes and tragedies that it is a question if there lived in Cincinnati during that period a man whose name was more familiar to the public eye.” [Cincinnati (OH) Enquirer, 4 May 1898: p. 8] He was described as a big, fat, jolly man, always ready for fun. De mortuis, one assumes. Plus he left three sons to carry on the undertaking business, who would be more inclined to advertise if the Enquirer didn’t rake up the past.

Freight and railway companies often found shipping the dead a very profitable line.

Replevying a Corpse

A poor widow had the dead body of her husband brought by rail from Dover to Leamington, without first inquiring the cost. The railway company charged at the rate of 1s a mile, making £8, and as the widow could not pay this sum they detained the corpse for two days until the money was raised. Evening Post, 14 May 1892: p. 1

HOLDING CORPSE FOR THE EXPRESS

The agent of the Adams Express Co. at Shamokin held the corpse of Henry Fretz, awaiting the payment of charges amounting to over a hundred dollars. It was finally settled by the government.

Fretz was from Pitman, Northumberland county, and an apprentice in the United States Navy. February 14 he was drowned in the San Francisco Bay and government officials notified his parents that they would bury the body there or bear the expense of having it shipped home.

The parents requested the body to be shipped and it arrived in Shamokin Wednesday evening, accompanied by a bill for charges amounting to over a hundred dollars. Being unable to pay the claim, the agent refused to turn the corpse over to the grief-stricken parents and it was held in the Shamokin office, where it remained until the tangle was straightened out by the government assuming the charges. Wilkes-Barre [PA] Times 27 February 1909: p. 9

Sometimes the writ was for a partial corpse.

Recently a man had his leg amputated in a Washington hospital, and, upon visiting the capital some months afterwards, discovered the member preserved in alcohol. He was shocked, and demanded it, that he might bury it. The demand was refused, but, upon bringing suit in replevin, the case was decided in his favour, and he was given possession of his own leg. The Arizona Sentinel [Yuma, AZ] 28 February 1885: p. 2

Here we find dueling replevins: for corpse and for shroud.

POLICE WILL GUARD FUNERAL SERVICES

Undertaker Threatens to Take the Clothes Off of a Corpse During Row With a Rival, So Precaution Is Taken

Funeral services for Charles Klytta, 60 years old, will be held under police protection this afternoon from his late residence, 5438 South Laflin street, because B. Trundell, an undertaker at 1702 West Forty-Eight street, threatens to interrupt the ceremonies with a writ of replevin and remove from the body a suit of clothes which he says he paid for.

This threat grows out of a dispute between two undertakers soon after Klytta fell heir to $1,000 several weeks ago. Klytta was employed by Trundell, but he was a close friend of Joseph Patka, 1750 West Forty-Eighth street, a business rival of Trundell’s.

When Klytta received the $1,000 he left his wife and eight children and went to live with Nicholas Jasnoch, 4858 Winchester avenue. Then he began to spend his small fortune in having a good time. He became ill and was told he had not long to live.

Immediately both undertakers asked Klytta if he couldn’t throw the “business” their way. Klytta was in a dilemma. He liked Patka as a friend, but also thought he should respect the wishes of his former employer. Finally a Bohemian lodge of which he was a member was asked to settle the question. A committee waited on Klytta’s death bed and argued the matter, with the result that Patka was chosen.

Scarcely had Klytta breathed his last, however, when Trundell drove up and carried off the body. Mrs. Klytta pleaded in vain for the return of the body. Then she engaged Attorney D. Carmichael, and he tried to get the body. Yesterday the lawyer obtained a writ of replevin from the Municipal court and, accompanied by a bailiff and a policeman, went to Trundell’s establishment. The body was laid out in state in the parlor, clad in a new suit of clothes.

The writ did not provide for taking the clothing with the body and an argument ensued. Finally Patka took the body and new suit and carried them off to his undertaking shop. Therefore Trundell threatens to obtain a writ of replevin for the clothing and to get it today when the services are held at the Klytta residence. The Inter Ocean [Chicago, IL] 8 November 1912: p. 1

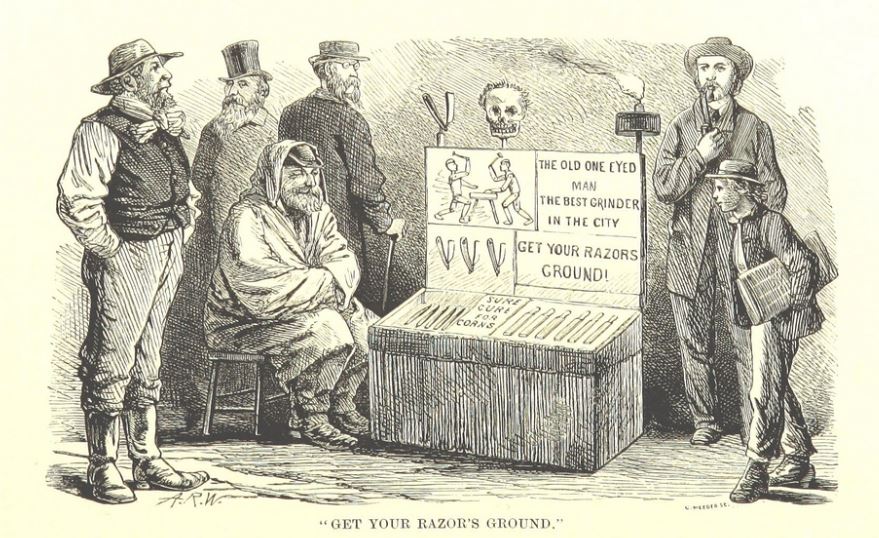

Undertakers more usually replevined their own property, such as coffins or candle-holders.

Bill Is Not Paid:

Takes Coffin Back

Detroit, Oct. 9 Because his bill for $300 had not been paid, Stanley Lappo, an undertaker, flanked by two constables, entered the home of Mrs. Vincent Dziegiuski. After retrieving the woman’s body from its casket, he loaded the latter, with candles, pedestals and display palms, into his wagon and drove off. The undertaker later explained the woman’s husband had agreed to pay the account before the funeral took place. When he failed to do so, Lappo obtained a writ of replevin and took possession of his property.

The husband later effected an arrangement with another undertaker, and the funeral was held a few hours later. Duluth [MN] News-Tribune 10 October 1921: p. 6

Sometimes the quarrels leading to a writ were not about money, but about something more visceral. This is an excerpt from the story of Mrs. Terrica Beck, an elderly Catholic woman badly treated by her daughter and son-in-law. I have not found a resolution to the case.

Throughout her last illness she desired to be buried in the Catholic cemetery. This was her last request. She died in her sister’s house. The expenses of her last sickness were borne by her sister. The coffin and shroud were purchased, and the last sad offices performed by her sister.

Scarcely had her last breath expired, when her son-in-law, before careless of her welfare, appeared and laid claim to her clothing and body. More desirous of the property, he departed expressing his willingness that Mrs. Beck’s dying wishes as to her interment should be complied with….In accordance with the wishes of the deceased, her body was placed in the vault of the Catholic cemetery, whence it was removed by a suit of replevin sued out by her son-in-law. He had obtained a coffin and shroud from the city, and had a grave dug at the expense of the city in the Potter’s Field. He was willing to pay the expense of a law suit, to defeat the dying wish of his wife’s mother, but not to pay for giving her more than a pauper’s funeral. Plain Dealer [Cleveland, OH] 28 April 1870: p. 3

One can only imagine the family dynamic that would lead to the following situation:

Refused to give up Body

Anderson, Ind., Jan. 4

Mrs. Joseph Speece was compelled to replevin the body of her husband so that it could be buried. He died Wednesday at the home of his wife’s father, John Nelson, and when she prepared for the funeral Nelson refused to give up the body until a large board bill had been paid. When a writ was served the body was delivered. The widow also sues Nelson for $100 for the detention of the body. Wilkes-Barre [PA] Times 4 January 1901: p. 1

One last oddity: Although judges in several jurisdictions ruled in the early 1900s that corpses had no commercial value (were not property) and thus could not be replevined, that judgement did not stand all over the country. In a 1906 case where there was a wrangle about the funeral expenses exceeding what the family wanted to pay, the family obtained a writ of replevin to get the body back from the overcharging undertaker. “As some value had to be given the writ it read ‘one corpse to the value of $50.’” The Cincinnati [OH] Enquirer 30 September 1906: p. 12

There are many dismal stories of first/second wives, mistresses, and hostile family members battling over loved one’s corpses, but they don’t always go as far as replevining. Other stories of legal proceedings over corpses? Swear out a writ to Chriswoodyard8 AT gmail.com

Thanks to Michael Robinson for the details of corpse property law.

Undine, of Strange Company, sent this great story of a legal fight over an embalmed body.

She also added a bonus tale of a dead-beat dad: A (somewhat) related story was about a man whose wife died, and he afterwards stiffed the undertaker on the bill. (“Stiffed,” get it? Oh, never mind) When, a while later, his daughter also passed away, this undertaker refused to take the job. In fact, he spread the word through the “Undertaker’s Association” that the man was a, well, deadbeat, so all his colleagues refused the man’s business as well. (As a side note, the bereaved man tried to get a free coffin from a local charity. When they realized he wasn’t indigent–just an incredible skinflint–they indignantly refused.) I don’t recall exactly how the story ended, except that he finally managed to get his daughter buried using a blanket instead of a coffin!

Thanks, Undine!

For more stories of Victorian death and mourning see my book, The Victorian Book of the Dead, also available for Kindle. Or ask your library/bookstore to order it. You’ll find more details about the book here and indexes here.

Chris Woodyard is the author of A is for Arsenic: An ABC of Victorian Death, The Victorian Book of the Dead, The Ghost Wore Black, The Headless Horror, The Face in the Window, and the 7-volume Haunted Ohio series. She is also the chronicler of the adventures of that amiable murderess Mrs Daffodil in A Spot of Bother: Four Macabre Tales. The books are available in paperback and for Kindle. Indexes and fact sheets for all of these books may be found by searching hauntedohiobooks.com.